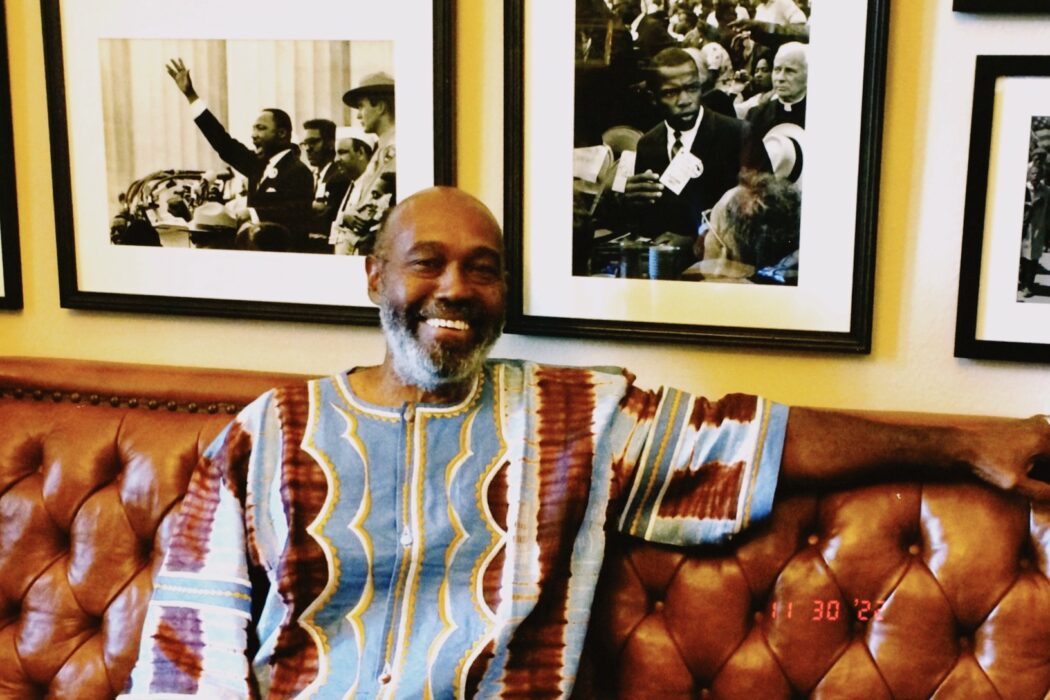

Bob Smith- History Maker

“As a teenager, I was a bit of a rabble-rouser, still am, I guess,” Bob said with a chuckle. Bob Smith was a civil rights leader in the 1960s and continues to advocate for what he believes in. On a first-name basis with the likes of those such as Congressman John Lewis and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Bob has lived and breathed history alongside some of the most beloved leaders of our time.

Meeting someone who has experienced history firsthand is not something that happens every day, so I asked Bob to tell me about his journey growing up in Mississippi in the 1960s during the civil rights movement.

“At 19, I got arrested for the first time in Jackson, Mississippi. I was trying to eat a meal at Woolworth’s restaurant. We were working on integrating the restaurant, and I got arrested along with the others.” Although this was not the first time Bob had a run-in with law enforcement, it was the first time he got taken to jail, “They put me in a paddy wagon, not a bus with the rest of the young folk that they arrested because they realized I was leading the charge. Then they took me to the outskirts of Jackson, and they stopped the paddy wagon and teargassed that sucker. I was the only person in that paddy wagon, and I thought I was going to die. That was the first time I got teargassed, not the only time, but the first time.”

After being teargassed, Bob was transferred to a new police car, where he was taken to a fairground to be held there, “They took me to where the other people were. They were all at a fairground, a couple of thousand young folk at the Jackson, Mississippi fairgrounds in cattle pins. And they held me there for a couple of days with the other people.”

Although days were going by, Bob did not give in, “I organized the people on the fairground to throw the food that was being given to us back at them. And we were singing. I taught them how to sing freedom songs.” He continued, “And the police recognized that I was the leader, and they took me from the fairground, put me in another paddy wagon, and took me to the city jail. And I was warned by others that when you get taken to city jail, you just get ready; you’ll get your butt whipped.”

Bob spent two weeks in jail, but little did he know what, or rather whom, was going to be waiting for him when he got out. When Bob was released, he was greeted by then civil rights worker, now more affectionally known as Congressman John Lewis. John stood outside the jail alongside a lawyer named Howard from New York who worked to bail Bob and 25 others out, and he simply said, “We are glad you are out of jail.” Afterward, John, Howard, Bob, and the others bailed out of jail that day, went to the United Methodist Church, sang freedom songs, and prayed, “That was my first recollection of meeting Congressman John Lewis.” Bob explained.

Bob spoke highly of Congressman John Lewis, looking at him as a peer and also a mentor, “John was four years older than me and a really good person.” He continued, “One time, I went over to John’s mother’s house with him, and at this time, he was a Congressman. And John’s mother asked him to run out to the store to get some sweet potatoes, so John and I went out to the store together to go get the sweet potatoes and John said, ‘You know, I’m a leader, but when I come home, I’m her son, and I am just John, and I just do what my mama tells me to do.’ At home, his role was to be a son. John was really grounded like that.”

Beyond the Congressman’s stand-up character, his leadership really stuck with Bob. Namely during the Selma March in 1965 on the day known as Bloody Sunday. “John Lewis and Hosea Williams led the Selma March on Bloody Sunday, where they were beaten on that bridge. John thought that that day was going to be the end of his life.” Bob took a deep pause and continued, “On that day when they marched from Selma to Montgomery, they had no real plan. How the hell did they think we were going to march 54 miles? But that is what they did. They just knew they were going to get started, and God would lead them along the way.”

Bob explained what his friend John Lewis shared with him about what happened on the bridge that day, “When John and Hosea got to the top of the bridge and looked over to the other side, John said to Hosea, ‘Man, they are really set up for us across the bridge.’ But they kept walking, and when they got to the other side, the sheriff said, ‘This is an illegal march, and you must turn around and go back to where you came from.’ Once the sheriff told them to go back to where they came from, John and Hosea knelt down to pray, and when they knelt down to pray, the sheriff ordered his men to charge at the marchers. They came at them with baseball bats with spikes. John has said many times that he thought that was going to be the end of his life, that he was going to die that day because they beat him so unmercifully.”

On that day, Bob was in Jackson, Mississippi, when he received a call saying that the sheriff and his crew had beat up the marchers, so Bob and his friends got four cars and drove from Jackson, Mississippi, to Selma, Alabama, “When we got to Selma about three hours later there were people still along the roads and on peoples porches who had gotten beaten and I stopped to provide first aid” Bob said.

That evening after providing aid to those who were beaten, Bob, the marchers, and other civil rights leaders and activists went to the Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma, Alabama, “We went to the Brown Chapel for a rally, and I was asked to speak to the people about what had happened that day. I didn’t mind speaking, and I sang some freedom songs too. At the time, I had a very good voice and don’t have much of a good voice anymore; I’m 77.” Bob proceeded to sing to me the song “This Little Light of Mine” – a song he had sung on that day. And I can assure you; he still has a beautifully powerful voice.

I asked Bob what made him so fearless at such a young age to get involved with the movement, “My parents and my church.” He continued to explain one of his first memories, “It started really young for me. At six years old, my school was set on fire and burned down because it was the colored school. The next morning I got up, got my books, and went to school even though I knew it was burned down. My dad and momma said, ‘Where are you going.’ And I said, ‘I’m going to school.’ And as I walked to school, I noticed I wasn’t the only kid doing it. There was a group of us. We were just walking down the street going to school, even though we knew it was gone. Nobody said a word. We got to the top of the hill, and we could see that the school was burned down. We sat there for hours together, all of us kids, and just looked at the smoke and the remains of the school.”

That was not the only experience Bob had in his youth that moved him to enact change in his community, “At seven, I got chased off of a white neighbor’s lawn and was threatened to be killed, and at 15, I was in line at the ice cream shop, and when a white person walked in, they got served first even though I was there before them.”

As Bob grew into a young man and became more active in civil rights leadership, he came across a man that really inspired change; Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Bob explains a time he met Dr. King, “We were at the Brown Chapel in Selma, Alabama the day before the Selma march and Martin Luther King Jr. spoke to the civil rights workers that day. He was the last one to speak and usually always the last one to speak. While everyone spoke before him, Martin would just sit there quietly and wouldn’t say much in the meetings. He would let people say what they had to say and truly listen to them to understand. Then at the end of the meetings, Martin would take what everyone said and sum it all up and create a plan of action. He was a true leader to people and always emphasized doing things peacefully and nonviolently. He was a humble man. A very smart man.”

Through years of activism, learning from some of the greatest leaders of our time, and then becoming one himself, Bob Smith has lived a life of honor and integrity. I got to know all of this while talking to Bob. I asked him what his advice would be to the next generation of leaders: “My advice to the next generation of leaders is to know your history, or else history will be repeated. Learn it and move forward. You don’t have to accept the status quo. Things are not always as they appear. Know your history, read it and prosper from that.”

Thank you, Bob, for taking the time to speak with me and for all of our efforts to create a better world through your work.