Robert J. Bernstein- The Supernatural Empath

It is not every day that you see a person walking around a gym holding a book and making enthusiastic conversation with everyone around them. Usually, most people are “in the zone” while working out and not really engaging with others—however, Robert Bernstein is not most people.

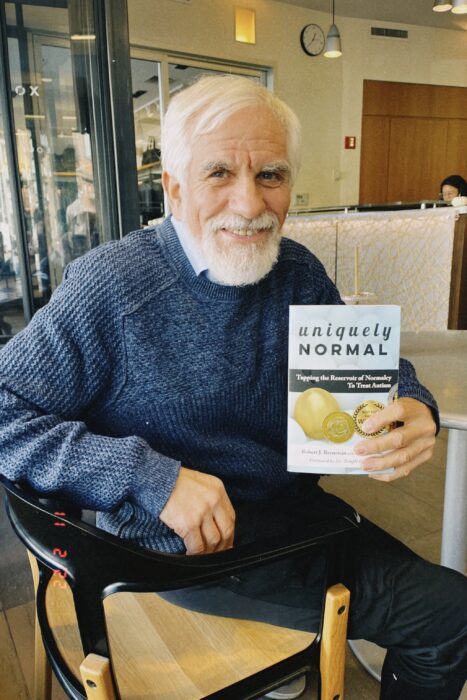

Robert approached me at the end of my workout, telling me he had just joined the gym. There was something childlike and curious about how he spoke, and he broke down the walls of each person he spoke with. It’s not often you witness people crack their focus in a workout to talk to a stranger. From the moment I sparked up a conversation with Robert, I knew he loved people and deeply understood and connected with them. As we talked, I looked at the book tucked under his arm. I could see the title of it peeking out, Uniquely Normal.

Intriguing.

I said, “What book is that?” He answered, “It’s my book; I wrote it!”

Naturally, I had to learn more about this quite amusing and naturally good-natured man, so I sat down with him at the gym and asked him about his book.

Robert released Uniquely Normal in 2017, and since then, the book has received several awards, including the prestigious IPPY award for independent publishing. Looking further at the cover, I noticed the subtitle, “Tapping the Reservoir of Normalcy To Treat Autism” I asked Robert to tell me how he found himself writing this book. He graduated from Columbia University Teacher’s College, where he studied Special Education, and has worked with children with intellectual disabilities over the last fifty years. He emphasized, “My whole life has really been devoted to this.”

Interested, I asked him why he chose to devote his life to the impactful work he does, “My brother is on the spectrum, and I saw how he was as we were growing up. Then when I went to college, I had a psychology teacher who recognized a talent in me. He told me I had a unique ability to capture how someone’s mind worked, that I could capture someone’s sense of self and help them see that. And with this part of myself, I have been able to understand the mind of autistic children. I try to understand the way they think and process information.”

With this talent, Robert has seen thousands of patients, all of who usually have some connection to autism, whether it is the children themselves or their family members. Robert’s gift lies in getting children to speak who have never spoken before and helping them effectively communicate their needs. Through years of research and hands-on work, Robert has developed and coined the beloved “Bernstein Approach to Autism” or the “Bernstein Method.” His method is sought out by professionals in his field around the world.

I asked him to explain his journey to finding the Bernstein Method, “About thirty years ago, I was working with this young girl. She was all over the place, and she couldn’t keep two things in mind at the same time. She couldn’t predict what to do next and was not taking direction from anyone. So, I very simply asked her to predict what she wanted to do. I wanted it to come from her point of view, not from my point of view of telling her what to do. So, she said she wanted to go on the swings and then go on the seesaw. And then she did it on her own. She got this idea that she could say what she wanted to do and then go do it. Habitually, she was all over the place, but now when she says she wants to do the seesaw next and then does the seesaw next and she does it on her own, something changes in the brain that it was her idea. That is the Bernstein method.”

Over the years, Bernstein has worked with some of the brightest minds in neuroscience and linguistics to understand children’s minds: “I have a friend, Dr. Steven Strauss, who is a neurologist and linguist. He understands the neurology of the brain better than anyone else I can think of in terms of development and language. I asked him, ‘Steve, when I work with kids between the ages three-five I see an incredible jump in terms of development; it is remarkable. When I see kids from the age of seven-ten, I see change, but it is not the same. Why is that?’ and Steve said, ‘The language part of the brain develops and stops around the age of six. In other words, the physiological development of the language part of your brain stops at six, and then other mechanisms take over.'”

This was when Robert realized that when he worked with children under the age of six, he could bridge a neurological gap. He explained, “So if I am working with a ten-year-old and see what he is missing, I know the gap happened when he was around two, and I can bridge the gap now, and maybe now they can become fundamentally stronger.” He expanded, “Another neurologist in New York approached me and said, ‘I know what you’re doing. You’re actually changing the brain mechanism; you’re actually having a physical change. You’re not establishing new pathways at a hardwire, but you’re changing the brain’s software.’ And that’s exactly it.”

Robert’s love for working with children’s minds was enthralling to hear about. He looked at two people sitting next to us and said, “If we were to observe these two adults right now, it would be pretty boring, but I find observing kids playing in their element fascinating.” He continued, “It’s amazing what these kids come up with, kids are very smart, and the system works against them sometimes. The whole problem with the educational system is that we have a curriculum. In a curriculum, someone is telling you what needs to be done, but for it to be truly effective, it has to come from the child’s point of view.”

This brought Robert to one of the strongest and most vivid memories of working with a child to implement the Bernstein Method, “I was called in to work with this boy who kept getting in trouble at school. He was getting kicked out of classes for causing a disturbance and would not listen to his math teacher, who was trying to explain to him how to do math problems. He would miss an hour and a half of school every day to get disciplined. And they said to me, ‘Bernstein fix this kid,’ and I always say don’t look at his shortcomings as deficits, forget about the deficit model which says, ‘Something is wrong with this person, and I am going to try to fix them.’ Instead, look at them as who they are and see how remarkable they are. Instead of making a cat a dog, try to make him the best cat.”

Excitedly, Bernstein continued his story, “So, I knew this boy loved baseball. So what did I do? I played baseball with him. As we played, I noticed that he caught the ball at the side of him, not in front of him, and anyone who knows baseball knows you don’t catch the ball to the side; you go right in front of the ball and catch it. So I went up to the kid and said, ‘You know I could show you a better way to catch the ball. Would you like that?’ He agreed, so I showed him how to catch the ball in front of him and said, ‘Look, I know why you catch the ball to the side; you’re afraid that the ball is going to hit you in the head, I thought the same thing too, but it probably will not hit you in the head.’ He then tried catching the ball in front of him, and he caught every ball where he was missing the ball beforehand. He thanked me, which very few kids do to me, so that is how I knew I got through to him.”

Robert simplified things for the boy, and as they were walking back to the classroom from playing baseball, Robert said to him, “When your teacher approaches you to do a math problem, she is doing the same thing I am doing with baseball.” The boy questioned Robert and asked him what he was talking about, and Robert said, “Look, I asked you if you wanted to know a better way to play baseball, and all that your math teacher is doing is showing you a better way to do the math.” Bernstein explained that he showed the boy a better way using baseball as an example that allowed the boy to see how listening worked with something he loved.

He resumed, “So now, Laura, this is the important part. I asked him, ‘What do you want the teacher to say to you?’ I want him to have control. I want him to feel like it’s coming from him.”

The boy answered, “I just want the teacher to say that she is going to show me a better way to do the problem.” So Robert told the teacher to say those exact words; he clarified, “Because how could the child misbehave now because he is in control? It is giving him respect. Kids are not respected because it is the whole, ‘I teaching you’ it’s not like they are a part of the process; they are not being included in the learning process. You can be the smartest teacher in the world and think you know what is best for the kid, but it does not work unless the kid buys into it.” The teacher used Bernstein’s method the next day, and it worked. The boy listened and did his math problems.

Once Robert identified his method, he said it took him five years to really believe it, to believe in himself, “There are so many great people who’ve established their approaches to autism, and I know I was different. I studied different approaches by different doctors and knew something important was missing in their methods. I wanted to bridge what was missing in those gaps. But it was hard for me to just accept that, like, wow, I have done that, and now I take ownership of my method.”

I smiled at Robert and told him I thought he was a supernatural empath. He chuckled and said, “I realize I have all of the best training, you know, I went to Columbia University and have spoken to the smartest doctors in the world, but it has to be effective to who the kid is.” Robert has this unique ability to observe beyond the academic and right into the true nature of humans. I shared that thought with him, and he agreed and then said with a grin, “It sounds ridiculous, but I really want to get out there and change the world.”

I don’t think it’s ridiculous at all. In fact, Robert, I would say you have changed the world significantly with your work. I’ll see you at the gym this week.

Robert is coming out with a new book in January 2023 called the Uniquely Normal Manual. You can find Robert and learn more about him and his work at www.autismspeech.com.